Explore a collection of archived d’vrei tefillah that offer fresh insights into the prayers we carry in our hearts and on our lips.

Each teaching invites you to deepen your connection to Jewish liturgy, discovering new layers of meaning that can transform your prayer experience.

-

This has been a big year for the moon. Fifty years ago, this past July, Neil Armstrong climbed down the ladder of Apollo 11, planted his foot in another world, and with half a billion people watching, proclaimed those immortal words—that’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind. Although I was just a very young child, possibly even in utero, I have vivid memories of that summer day in 1969. (ask who else, share reflections)

For as long as humans have turned their faces upward to marvel at the celestial bodies, the moon has held a special mystical magical fascination for us; we’re drawn to its silvery, luminous light like, well..like moths to a flame. Poets and artists have romanticized the moon for ages, and singers of love songs are wont to croon moony tunes. (Moon River, Shine on Harvest Moon, Fly Me To The Moon, Bad Moon Rising, Moonshadow),,,Aristotle and other ancient Greek philosophers believed that Luna, the Roman moon goddess, used her power for evil to drive people mad—I offer you the word “lunatic” for your consideration. Dogs howl at the moon, werewolves are transformed during a full moon—seems like humans and animals alike (even ones of folklore), are all moonstruck. (awesome movie, btw).

In Judaism, we are no less fascinated by the precise cycle of the waxing and waning of the moon. So much so, that our calendar is based on it. The Jewish calendar is a complicated affair in which the rabbis developed an intricate system of adding extra months so that each holiday would fall in its appropriate season- the lunar year is 11 days shorter than a solar year, and so we have extra months and leap years and all kinds of stuff to compensate for the shortfall. Wouldn’t it be easier to just go by the solar calendar?? The calendar is so central to Judaism that it is the first commandment the Jews were given as a nation. Prior to leaving Egypt, God instructed Moses: “Ha Hodesh Hazeh lachem rosh hodashim rishon hu lachem l’chadshe hashanah. This month shall mark for you the beginning of the months; it shall be the first of the months for you” (Exodus 12:2 Bo). An earmark of slavery is that the slave has no control over time; therefore, in order to truly leave the servitude of Egypt, the Israelites had to be masters over their own time.

So taken are we with the lunar cycle that we have not one, but two monthly rituals associated with it. The first one is Kiddush Levana, or sanctification of the new moon. Each month, shortly after the appearance of the new moon, special blessings prayers are recited in praise of the moon’s renewal—this is not to be confused with bentsching Rosh Hodesh, which I’ll get to in a minute. The ritual of Kiddush Levana takes place at night, outside, in the light of the moon. It includes the recitation of psalms and some rabbinic blessings recorded in the Talmud. Abayye, one of the great rabbinic sages of the Talmud, noted that the recitation of Kiddush Levana is so great a mitzvah, that it is to be said standing, and that “whoever blesses the moon in its proper time is considered to have greeted the Shekhina itself; that the renewal of the moon each month reminds us of the magnificent wonder of God’s creation. Another interpretation suggests that just as the moon is constantly in a cycle of increasing and then decreasing in size, so too, historically, the Jewish people have gone through similar cycles, experiencing ‘lows’ only to re-emerge refreshed and rejuvenated like the moon.

If Kiddush Levana is about sanctifying the glory of God’s creation, Rosh Hodesh is a more human matter. On Shabbat Mevarchim, which is the Shabbat immediately preceeding Rosh Hodesh, we express our hopes for the upcoming month. We pray that it will be a month filled with peace, goodness and blessing, physical vitality, abundance and honor, and that we will be free from shame or reproach, and that with a full heart we’ll be guided by the love of Torah, and all our worthy aspirations be fulfilled. …… Now, I LOVE bentsching Rosh Hodesh. It’s quite a grand affair—the hazzan stands, flanked by sifrei Torah, and the public announcement of precisely when the new month will start is done with a mixture of fanfare, gravitas, and joy. But that’s not why I love it. I love it for what it stands for-an opportunity for renewal. Built into the fabric of our tradition and ritual, Judaism affords us so many opportunities for renewal and rebirth (I love that about us..) Every year,we get to do this 11 times, monthly. Except for one month. Tishrei. Tishrei is the only month that we don’t bentsch Rosh Hodesh. Seems paradoxical, no? I mean, of all the months not to herald with fanfare and flourish…on the surface, it feels like Tishrei is getting the short end of the stick, especially since the whole month is essentially yontif. Tishrei is the poster child for renewal and rebirth; we beat our breasts and cast our sins away and and pray that teshuva, tefilla and tzedaka can mitigate our destiny. The Ba’al Shem Tov explains that there is no Shabbat Mevarchim for Tishrei because “ HaShem blesses the month of Tishrei on the last shabbat of Elul—and the remaining 11 months of the year are left to be blessed by the Jewish people, that Tishrei alone has the z’chut, the honor, of being blessed by The Kaddosh Baruch Hu, and that makes Tishrei unique, and sets it apart from the other 11 months of the year. (ask for reactions). Ok. Nice. But, I was not completely satisfied with that explanation so I went looking a bit further. And I came across an idea of Rabbi Shmuel Bornszstain, the second Sochatchover rebbe, in his Shem Mishmuel. Here’s his reasoning. The Shabbat that precedes Rosh Hodesh logically belongs to the previous month. So Shabbat Mevarchim actually serves as a bridge, in that it connects one month to the next; it draws some of the sanctity of Shabbat into the new month. RH, however, commemorates God’s creation of the entire world, ex nihilo, from nothing. We, in our efforts to achieve godliness, seek to imitate God’s creation of the world, by creating our new year, from nothing. We do not bless the new month of Tishrei, therefore, because we don’t want a carry over of any baggage from it with us, so that we can create our new year, free and clear, without any connection to what came before. Rabbi Bornzstain holds that in this way, we have an extraordinary opportunity to begin anew; we can start our year with a totally blank slate, just as the Kaddosh Baruch Hu began the world.

This has been a big year for the moon. This past April, a few weeks before Yom HaShoah, Beresheet, the Israeli unmanned lunar lander, attempted the reach the moon. Though technically unsuccessful, Beresheet managed to snap this photo (show photo) before crash landing on the moon—only the 4th country in the world to do so. From the ashes of the Shoa, the state of Israel has risen to unimaginable heights in search of rebirth and renewal. May 5780 be a year in which we are able to rise to new heights of limitless potential, boundless joy and everlasting peace. Keyn Yehi Ratzon. I wish you all a Shanah Tovah Tikatevu -

Start with niggun—rh ma’ariv.

It was RH. Everyone had come to the synagogue to welcome the new year with prayers. Everyone was hard at work trying to really mean every word they were reading. From the back of the synagogue there was a whisper…alef, get, gimel, dalet. At first, it was very quiet, almost no one noticed. Everyone was paying close attention to the machzor while the hazzan chanted the prayers. But over and over from the back of the room, came the whisper, alef, bet, gimel, dalet.One by one, people began to turn and look to see the whisperer who was interrupti ng the service. Sitting at the back of the congregation, in the very last row of the synagogue, was a young boy. He was standing with an open machzor, saying over and over again, alef, bet, gimel, dalet. Soon, all the praying had stopped. Even the rabbi had stopped praying. The boy didn’t notice.Every person in the synagogue was looking at him, but his eyes never left his Mahzor. Over and over he said, Alef bet, gimel dalet. Suddenly, the boy looked up. He was very scared. He was almost about to cry when he said. “I don’t know how to read. All I know is the first four letters of the alef bet. Today is a day when all Jews must pray. So I have said my four letters over and over, hoping that God will make them into a prayer.” The rabbi of the congregation walked down the aisle and hugged the boy. She said. Today we have been taught the meaning of prayer. The words in the machzor are important But really, opening our hearts to God is most important. If we don’t know or understand everything, we should at least feel our prayers, and say them with honesty. Then she said, Let us pray together. Everyone in the congregation joined in saying, alef bet, gimel, dalet.

For the past several years, I have had the very great privilege of addressing you from this bimah, to share a few insights about a carefully selected prayer. This year, I decided I’d go for broke, and talk about, well…prayer itself. The little story I just told you brings to light the classic struggle in Judaism known as keva vs. kavannah. Keva refers to the specific laws regarding prayer, the what, when, how to pray. The importance of Keva is that it gives us a framework for God language, and helps us cultivate not only our relationship with God, but also our relationship with our inner selves. Keva takes the guess work out of prayer, and helps us to practice Godtalk. But, when you say the same prayers, day after day, season after season you run the risk of them becoming routine, of losing their meaning. Seemingly in polar opposite to Keva, is Kavannah, or intention.

Berachot chapter 5 Mishnah 1 has this to say about Kavannah (with apologies to the rabbi for working her side of the street)

אֵין עוֹמְדִין לְהִתְפַּלֵּל אֶלָּא מִתּוֹךְ כֹּבֶד רֹאשׁ.

“A person should not stand up to pray unless he is in a serious mind-frame. The original pious ones used to wait one hour and then pray, in order to direct their hearts towards the Hashem. [When reciting the Amidah,] even if the king greets him, he should not respond to him, and even if a snake wraps around his heel, he should not interrupt”….

Abraham Joshua Heschel said,” prayer is worship of the heart, the outpouring of the soul, a matter of devotion. So, according to Heschel, Jewish prayer is guided by two opposite principles: order and outburst, regularity and spontaneity, uniformity and individuality, law and freedom. These principles, Keva and kavannah, are the two poles about which Jewish prayer revolves. Since each of the two moves in the opposite direction, equilibrium can be maintained only if both are of equal force. The fixed pattern and regularity of our services tends to stifle the spontaneity of devotion. Our great problem, therefore, is how not to let the principle of regularity impair the power of devotion. He who is not aware of this central difficulty is a simpleton; he who offers a simple solution is a quack. “

Now, far be it from me to contradict Heschel., and I very well may be a simpleton and a quack..but I don’t think that keva and kavannah are necessarily diametrically opposed. In fact, I think they work in concert together with one very important element. Music. Deuteronomy 31:19 parshat Vayelech says ועתה כתבו לכם את הש'רה הזאת ,ולמדה את בי ישראל שימה בפיהם

Therefore write down this song for yourselves and teach it to the children of Israel and put it in their mouths..

Before its writing is completed, embedded in the Torah is the directive for a still nascent Israel to make of all of Torah a song, establishing the primacy of music in the symphony of Jewish life. Because music can reach those parts of the human soul that text alone cannot; an infectious rhythm can make you snap your fingers and tap your toes; a beautiful melody can bring an inexplicable tear to your eye or a lump to your throat. Jewish music in particular, dates back thousands of years to the Temple, and is inextricably woven into the fabric of Jewish culture, ritual, and tradition.

So what does all of this have to do with making prayer meaningful? Our sacred liturgical texts reflect the beauty of the rhythm of Jewish life. Nusach Ha-Tefillah, the traditional musical prayer modes, drives that rhythm. It is the alarm clock of the Jewish people, telling them the time of day, day of the week, season of the year. (demonstrate with chatsi kaddish for chol, shabbat, etc). And knowing that for centuries, Jews around the world have listened to the same haunting melodies of Kol Nidre , or the romantic cantillations of shir ha-shirim trope on the regalim, well, I might not understand all the words, but the melodies go straight to my soul. And for me, that is meaningful, and connects me to something larger than myself.

We’re living in troubled times. The world is a frightening, disheartening place at the moment. So maybe it’s a little frivolous for me to be standing up here, talking to you about music. But it’s my tool of trade; it’s how I make sense of and in the world. And it doth have charms that soothe the savage breast. And those seem to be in particular abundance in the world at the moment. So why not music? The great Yiddish novelist Y.L. Peretz observed, “the whole world is nothing more than the singing and the dancing before the Kaddosh Baruch Hu. Every Jew is a singer before God. And every letter in the Torah is a musical note.” My job as Klei Kodesh, is to move the words of our sacred liturgy right off the page and into your heart, so that we all may become singers before God, as we pray together, alef, bet, gimel, dalet. -

Last year, I stood here on this bimah, and explained to you all how my family and I were in a state of pre-traumatic stress disorder—waiting, with great trepidation and anxiety, for that dreaded phone call that would signal the end of my mother- in- law’s life. In the course of this last year, in my family we’ve experienced the death of a matriarch, the birth of a grandchild,(not mine), the wedding of my son and wonderful new daughter-in-law, and we’re looking forward to a bar mitzvah in a few month’s time. What a difference a year makes, and what a year it has been. Rather than filled with dread, I am filled with gratitude. Exhaustion----and gratitude. I’m grateful for the year that has passed, and I’m grateful with anticipation for the year ahead. And I’m especially grateful for Rabbi Bogatz, who for the past 3 years has been such an inspiring and generous clergy partner, who has allowed me this sacred time and space, to learn with all of you.

In just a few moments, we’ll recite the Unetaneh Tokef prayer.It is a prayer rich with powerful imagery, and, for me anyway, terrifying and challenging theology. Unetaneh Tokef, kedushat hayom. Ki hu nora v’ayom..We give power to the sanctity of this day, a day filled with awe and trembling. Emet ki Atah Hu Dayan Umochiach, V’Yodea Va’ed. V’chotev, v’chotem v’sofer u’moneh. You, God, are the one true judge. You record, you seal, you count and measure all of the deeds that we ourselves have forgotten. You open the Book of Remembrance that each and every one of us has signed with our deeds. –v’chotem yad,kol adam bo. Our sense of doom grows as we are told, “B’Rosh Hashanah yikateivun. U’v’Yom tzom Kippur yechatemun.” On Rosh Hashanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed. And what follows is a litany of either good endings or horrible fates.

Now, I don’t know about you, but to me this is pretty terrifying. There’s a book?? With a record of every bad thing I’ve done?? How long is this book?? On the surface it’s a difficult prayer. It seems to reflect a theology that is difficult if not impossible for most of us modern Jews to believe, a prayer addressed to a kind of “Santa Claus” god who records our deeds, sees who is naughty and who’s nice, and then inscribes us for good or bad in the year to come. But in fact I think that this prayer is more complicated than that. In language that might sound a bit foreign to our ears, Unetaneh Tokef attempts to get at a fundamental spiritual and existential truth that speaks to us every year. K’vakarat roeh edro, ma’avir tzono tachat shivto. The powerful imagery of the second paragraph of this poem likens us to sheep, mindless and helpless, passing before God, our shepherd, as we are counted and made to pass under God’s staff, and God’s scrutiny. I would coach this piece of text endlessly with my teacher and mentor, Cantor Lawrence Avery, z”l, and he would tell me to “make this part scary.” I’d like to suggest, however, that unetaneh tokef empowers us to act as God’s partner, not as God’s subject. For we know that in this world, the wicked often succeed and the good often suffer. The power of Unetaneh Tokef does not come from its literal meaning. On the contrary, used as metaphor it has the ability to put our lives in perspective and gives us the opportunity to listen to our hearts. Uvashofar gadol yitaka, vkol d’mama v’daka, yishama. The juxtaposition of the external cry of the great shofar and the internal still, small voice, is a gorgeous, poignant message. God speaks within us, if we are careful and choose, to listen.

We control freaks live in the cloud of chaos, similar to that primordial chaos that preceded creation, and Unetaneh Tokef speaks to that. We are not in control of many things. Who knows what’s going to happen? The only things that we can control are the ways that we respond to the world: through inward turning teshuvah, through upward turning, tefillah, and outward turning tzedakah. If you think about it for a moment, contained in these three words is Jewish spirituality in a nutshell, and the ultimate message contained in unetaneh tokef. Real faith is not expressed in theological constructs, but in what we do and how we choose to live.

Over the course of the Yamim Noraim, we’ll hear Unetaneh Tokef 3 times. Take note of the crescendos and the moments of quietness in the melody and in the content of the words. Give into, momentarily, the terrifying images it creates. Allow yourself to become afraid and moved by the second paragraph, which expresses the awesome fear we may have when being scrutinized by God. And then allow yourself to be brought back to this world, and attempt to really mean it when together we raise our voices and reveal the ultimate message of kedushat hayom : u’ teshuvah, u’ tefilah u’tzedakah ma’avirin et roah hagzera – that repentance, prayer, and righteous giving will avert the severity of the decree by bringing meaning to our lives. This one prayer is a microcosm of the whole High Holiday season. It leaves us simultaneously exhausted and in new spirits. I hope that with the help of this prayer, we will be able to push the re-set button and bring our deepest-held values back to the forefront of our lives. L’ Shanah Tova Tikateivu V’Tikatemu—may we all be inscribed in the book of life for a year of good health, a year in which we can be attuned to the unique melody of our own still, small voice. -

Recently, my son Max and his girlfriend Sarah, infected me with Hamilaria. And as a result, I am now obsessed with Lin Manuel Miranda’s epic musical, Hamilton. I haven’t seen it, but I know the entire score; I am moved by the lyrics and music like none other I have ever experienced, and I just want to invite Lin Manuel for Shabbos dinner. Early in the first act, George Washington is trying to get Hamilton to be his right hand man. Young Hamilton, a bastard orphan, is obsessed with rising above his humble impoverished beginnings, making his mark, and leaving a glorious legacy. Washington tells him, “Dying is easy young man. Living is harder. Let me tell you what I wish I’d known, when I was young and dreamed of glory. You have no control who lives who dies who tells your story.” What an artful, poignant echo of U’n’taneh Tokef (Lin did, after all, grow up in Washington Heights), and of how precious is life, and how we all yearn for that which is unattainable-immortality.

This past summer, Dorothy Parker would’ve been 123 years old. As a critic and famed member of the Algonquin round table, Parker is remembered for her acid wit, those critical and epigrammatic barbs that were constructed so well they were poetry in their own right. On writing, Parker quipped, “I hate writing. I love having written.” And, “writing is the art of applying the {tush} to the seat.”

Such has been my mindset whenever I would think about writing this drash. Because, despite Ms. Parker’s 123rd birthday, this past summer was a particularly crappy one for my family. As I sit writing this, my wonderful mother in law, is lying in a hospice in London, where she has been since the end of July. And my wonderful husband, has been with her since then, with only a few short trips home for a few days now and then, and I commuted back and forth across the pond a few times in between. Every early morning or late night phone ringing made me jump, the feeling of dread instantaneous in the pit of my stomach. For months we’ve been living in a weird, existential state of limbo, trying to go about living life while ever mindful of the precariousness of our situation. I was anxious about making plans or seeing students or taking on obligations, or even being able to serve here for the Yamim Noraim. Ask Rabbi Dana. We were living, all of us, with a kind of “pre-traumatic stress disorder.” But then again, who isn’t? Our world is unstable and unpredictable, and despite scientific and technological advancement, operates to a great degree, outside of our control.

My grandfather, Max Cooper, z’l, had a favorite saying, some folk wisdom from Odessa.(insert Russian Jewish accent) “Ellenu,” he would say to me, when I was all twisted with teenage angst, “Everything is nothing.” Which loosely translated means, don’t sweat the small stuff. He was quite the philosopher, my beloved poppa, and so I named my firstborn after him. My mother, z’l, entrusted me with his diamond pinky ring, with instructions to give it to my son Max on his 21st birthday. Which I dutifully did, 4 ½ years ago, and then I took it back, because what does a 21 year old boy need with a diamond pinky ring?

About a month ago, Max came home, and asked for that ring, and told me he was going to propose to his girlfriend. They had been dating for several years, and to us she was already our daughter, and my heart leapt with joy and did the happy dance. When I asked him when he thought he was going to do this, his response brought me up short. “After the shloshim,” he said. And I broke the cardinal rule. I meddled. I told him that not only was that kind of creepy, as Booba was still alive, but you don’t delay a simcha, and most important, she would be overjoyed to hear the news, so on the contrary, hurry up and get on with it. Thankfully he listened to me, and so now Max and Sarah are officially engaged. And as full of joy as my heart was, and is, I spent the next several days in quite a weepy state, wishing that I could share this naches with my parents, and because my precious child probably wouldn’t have a grandparent under his chuppah.

With the proverbial book of life still open before us, the metaphor this yom tov is especially poignant, and the words of U’netaneh Tokef haunt me. B’Rosh Hashanah Yikateyvun. U’v’Yom Tzom Kippur Yechataymun. On Rosh Hashanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed. How many shall pass on from this world, how many will enter into this world. Who will live and who will die? Who in the fullness of years, and who before her time? Death happens, whether we like it or not, and no matter how prepared we think we may be we never are. What most of us regard with dread-death, and its cousins-old age, illness, accidents—hang over us all, and yet, they can be the ultimate teachers in helping us learn what it means to be alive. The sage, R. Yehoshua instructs his students, “Repent one day before your death.” The students rightly reply, “How do we know what day that will be?” And the rabbi’s wise response? “So? Make it today!” But most of us don’t. WHY? Because it’s easier to go through life denying death, thinking we are invincible. But then, we arrive at the Yamim Noraim, and we are brought face to face with our worst fears.

In the thirty years that I have loved my MIL, she certainly seemed invincible—walking over a mile to and from shul when she came to visit—well into her 80s. Rising earlier and going to bed later than anyone else in the household to cook for an army, her limitless love and patience for her children, grandchildren and great grandchildren; serving for decades in the chevra kadisha for her community. She never misses an opportunity to bestow an act of chesed— she begins and ends every sentence with “Baruch HaShem,” my MIL understands the precious gift that is life--of course a woman like that would live forever!

It’s taken me 2 pages to get to what I want to talk about this evening. That’s why I’m a hazzan, not a rabbi. I want to talk about Kaddish. There are several different types of kaddishes-chatzi kaddish is included in every other kaddish and serves to punctuate divisions in the service—like before barechu and the Amidah. Kaddish Shalem separates larger parts of the service, Kaddish d’Rabbanan, after learning a piece of Torah. But chances are, when hear we the word, “Kaddish,” we all automatically think of Mourner’s kaddish, or Kaddish Yatom-literally translated as “Orphan’s Kaddish.” We’ve all heard this Kaddish referred to as a prayer for the dead, when in fact, nothing could be further from the truth. Kaddish is a prayer for the living, for the mourners who are left behind, as a reminder that we are a link in a chain of past and future generations. The essence of Kaddish, the public response of Yehe shmay rabba mevorach leolam ulmay al maya, “May the greatness of God’s name be praised forever and ever” gives us the formula to praise God and give thanks for life and faith, even at a time of profound sadness and loss, when it is human nature to despair God and faith. Let’s face it—few of us will feel gratitude for the greatness of God while standing at an open grave. But Kaddish is about striving for immortality by reinforcing the memories. It is about finding a heart of gratitude even in loss. It’s about finding joy after the loss. It’s about trying to become better, not bitter.

On Rosh Hashanah, Rabbi Dana spoke to us about the importance of community. Kaddish is the embodiment of this. Traditionally, we need a minyan to recite mourner’s kaddish. Now there are a lot of theological explanations for this—don’t ask me what they are, I told you, I’m a hazzan not a rabbi, but the overarching reason is that no one should be left alone with their grief. Grief, a time of great personal distress, in Judaism requires a public response. Each of us carries unique memories. No one’s story is exactly the same. We think that no one can really understand the depth of our sorrow, what it means to lose a loved one who has meant so much to us. My mother, z”l, used to tell me, “nobody gets through life unscathed.” It is eleven years since she has passed, sixteen for my dad. I miss them every day, sometimes as a dull ache, other times as a sharp pain. They both hurt. Grief isn’t something that one “gets over,” rather we must learn to live with it. And from it, if we are fortunate. The longer I live, the more I am certain that’s what she meant.

Tomorrow, we will gather together for Yizkor. Alone, we all know pain. But in our mourning and sorrow, we discover our shared bond. Grief is universal. Together when we stand in support of each other, we can bear any burden. May this holy time of remembrance remind us that when we are in need of strength, when we are in need of comfort, we can find it in the open and loving arms of family and friends. And in the rich, poignant melodies of our tradition. The Sages taught—“Life and death are separated by a very thin veil.” At a time like this, during the Yamim Noraim, when generations mystically merge, that veil seems virtually transparent. May the words of our Kaddish empower us to embrace the life we are given, filling it with love, inspiration, awe, gratitude, and remembrance. In Star Trek II, the Wrath of Kahn, Dr McCoy tries to console Kirk after the death of their friend, Spock. “He’s not really dead, as long as we remember him.” McCoy’s take on immortality is subtly different than Washington’s as he addresses the young Hamilton. While it is true that we have no control over who lives or dies, we have absolute control over how we live that precious life, which in turn impacts how we are ultimately remembered. Perhaps Max and Sarah will have his grandparents with them under the chuppah after all.

G’mar Chatimah Tovah. -

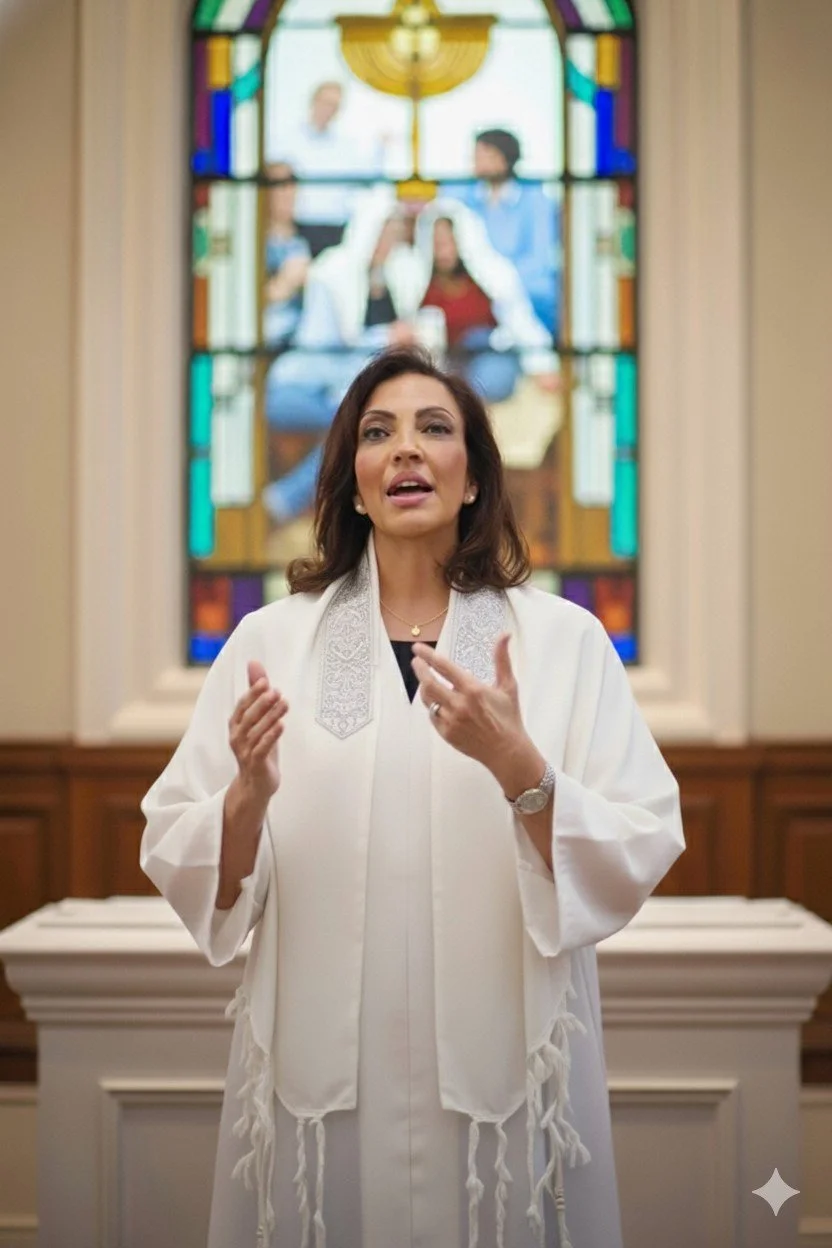

In a few moments, I will take my place, at the very back of the room, and begin the “Hineni” prayer—one of a special category of tefillot called reshuyot—where the leader asks permission of God to pray on behalf of the congregation. Hineni, whose authorship is unknown, is perhaps the most well-known of these. It’s an interesting word, hineni-here I am—especially this time of year, when we are attempting to renew and re-connect to God, to each other, and to ourselves. Someone reaches out, someone reaches back. Hineni implies a relationship-it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is an offering of the most intimate nature. An offering up of oneself, with everything that entails.

Here I am, impoverished in merit, frightened and trembling before the glorious presence of God. Although I am unfit and unworthy for the task, I have come to represent Your people Israel, and plead on their behalf. Do not hold them responsible for my shortcomings. Chanting Hineni takes both chutzpah and humility, a very tricky balance (especially for a hazzan).

As I sat down to write this, there was my own version of Hineni rattling around in my head.

Here I am, charged with speaking to you, about the meaning of this day, about God, about Torah. It is an awesome and intimidating task-to find the right things to say, to be a proper conduit through which others can make meaning from tefillah. I ask for clarity in the face of confusion, so that I can be guided, and in turn, be a guide for others.

Tomorrow, we’ll read the story of the Akedah-the Binding of Isaac, and we will hear the word Hineni 3 times. “Avraham,” God calls, “Hineni” Avraham responds.”Father” says Isaac, “Hineni b’ni—here I am, my son.” A malach, an angel of God calls to Avraham-“Avraham, Avraham!”and Avraham answers, “Hineni. Here I am.” Avraham has answered Hineni 3 times: responding to God, his parent, Isaac, his son, and perhaps to himself as he realizes the horror of the sacrifice he was saved from committing. In each of these instances, Hineni is linked to an intensive decision, a life-changing moment. It is uttered with mindfulness and deep reverence for that precise moment and its full impact. It is built on an intricate awareness of self and surroundings, reverberating intentionality and conviction. We encounter the same kinds of “hineni” moments in our daily lives. There are those who will answer “yes,” before they even hear what is asked of them. They are ready, they are present, no questions asked. To be willing to say “hineni’-here I am, is to be present. Because, what else do we really have? I serve as a chaplain at New York Presbyterian Hospital. The singlemost important affirmation of chaplaincy is to be present. I can’t fix a patient’s problems. I can’t take away their suffering. But I can be present, with my full self, to all that they are, all that they are going through, and through my presence they know that they are not alone. That someone is witnessing their life. Their suffering. That they matter.

This is what I have to offer you. This day is a day whose theme is God’s Majesty, and human surrender. When you hear “Hineni” this year, let the words and music seep into you. Allow yourself to be fully present for a transformational moment. And then, for the rest of the year, my hope and prayer is that each of us be privileged to hear a call to which we can respond, “hineni”-not out of fear, like Avraham, but because we have been transformed and have brought ourselves to a new place of being fully present for those in our lives.